Not Your Average Garden Hose Part 1

With guests Søren Thustrup and Adam Rubin

Mar 19, 2019

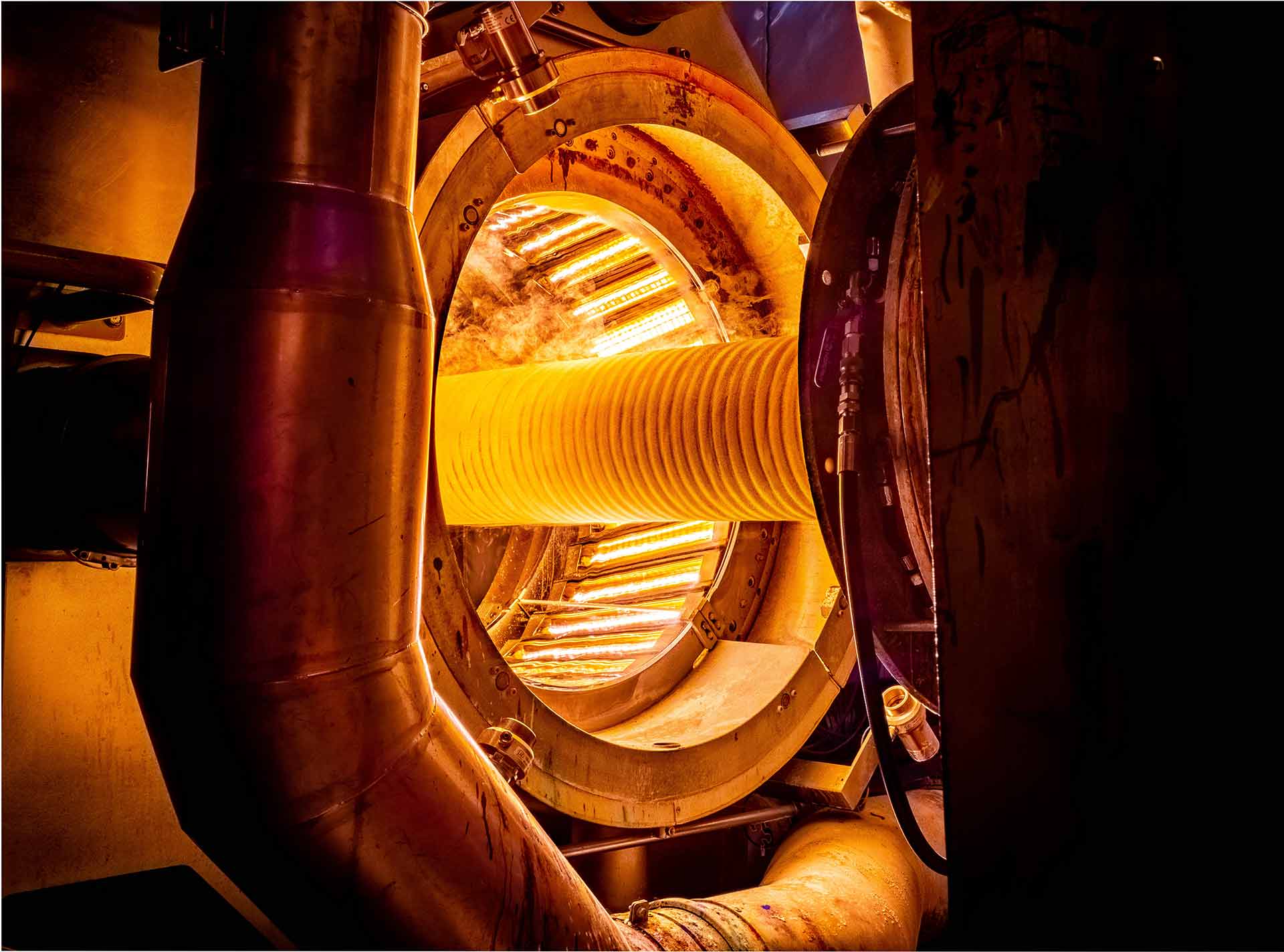

What if a technology used in the oil and gas industry had to operate flawlessly for 30 years in some of the harshest, most demanding environments on the planet, but it could only be inspected once during that period? On this episode of our "Four Corners" series, NOV Today host Michael Gaines travels to Denmark to visit our Flexibles facility, where he learns that our subsea flexible pipe is just that. Listen in as we explore how superior manufacturing and technical know-how are helping us to give operators peace of mind that their asset will survive for decades despite the challenging ocean conditions.